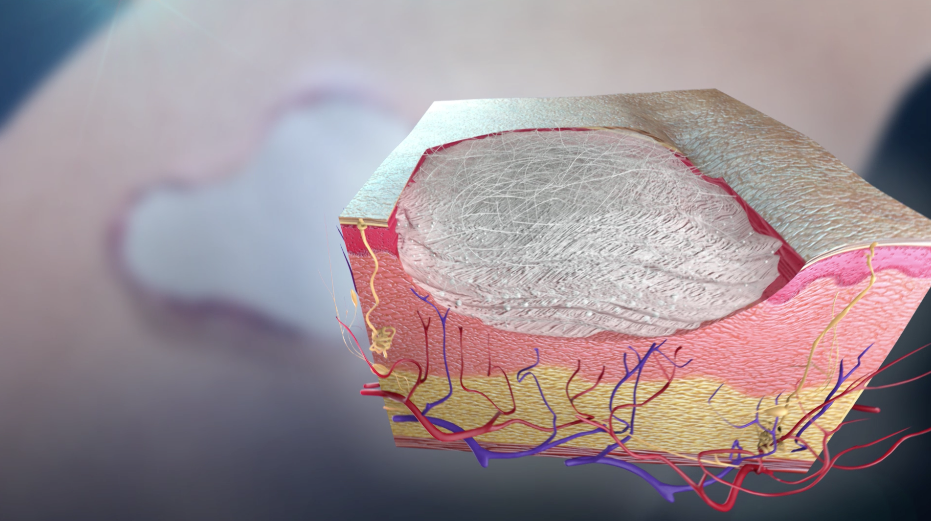

Wound healing is a complex and dynamic biological process that requires different types of cells to complete the critical steps at the appropriate time promptly1. When blood vessels are damaged, they constrict and dilate intermittently. The vessels must constrict to stop blood loss and then dilate again to allow the immune system deal with the invading microorganisms such as bacteria. A scaffold is then formed by a network of fibrin, allowing a proliferation of new cells to again populate the site of injury.

Wound healing is usually taken for granted; however, there are many factors that can affect this complex process, such as medications, infection, and lack of oxygen. Age and diabetes are considered the top risk factors for impaired or delayed wound healing.

Diabetes and aging can result in blood and other body fluids that accumulate in the lower limbs and feet owing to damaged valves or stretched veins, and therefore prevent these fluids from being pumped back to the heart. When more and more fluid accumulates, it increases the pressure which, in turn, causes the accumulated fluids to seep through the skin. This triggers a venous stasis ulcer.

The fluids that seep from the wound include enzymes that clean a wound during the early stages of the healing process. However, when these fluids exude continually, they impede the next step of the healing process and make the wound even worse. In many cases, limb amputation1 provides the only solution for treating repeated infection and long-term non-healing wounds.

About 1% of people in industrialized countries suffer from leg ulcers, which are mainly attributed to poor flow of blood from the legs to the heart. In spite of treatment, some ulcers do not heal even after months or years. As a result, intense research has been made on specialized wound-care treatments capable of promoting the healing of leg ulcers.

Specialized wound-care

Fluid accumulation can be prevented through compression of the lower leg. This can stop the fluid from seeping through a venous stasis ulcer and allow the wound healing process to carry on2. Likewise, fluid accumulation in the wound can be prevented by applying a vacuum to the ulcer, and thus promote the healing process3.

While these approaches can be effective, they are very expensive and have to be continued for an indefinite period of time, and most importantly, they are inconvenient for patients. Further, there is no guarantee that wound healing will be achieved.

One innovative wound care approach is adding glass fibers to develop a scaffold that promotes the formation of new tissue and thus helps in wound closure4. This scaffold is similar to the natural scaffold provided by fibrin during the wound healing process.

Bioactive glass in tissue engineering

Over recent years, breakthrough developments in tissue engineering have made it possible to reverse the damage caused by disease or trauma5. A temporary biomaterial scaffold that provides the required shape or support while the new tissue grows represents an important aspect of all tissue engineering. Bioactive glass, in terms of its strength, biocompatibility, and range of attainable properties, is broadly used to extend support in tissue engineering.

So far, silica-based bioactive glasses have been traditionally used to facilitate periodontal reconstruction or bone repair, but now many new borate-based bioactive glasses are used as scaffolds for soft tissue engineering5. Borate bioactive glass scaffolds provide the required support and have also been shown to promote angiogenesis, a key process that promotes the growth of new tissues5.

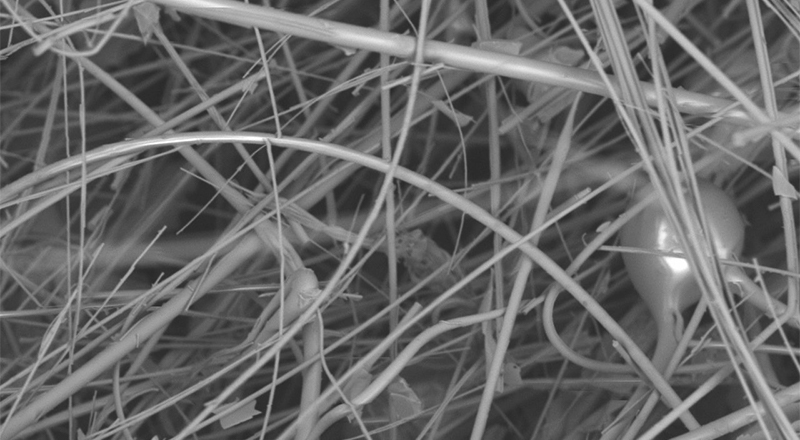

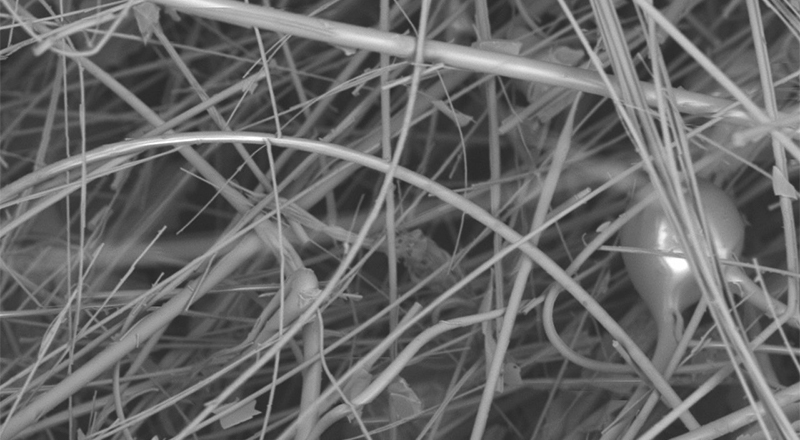

Recently, a new form of borate bioactive glass has been developed by Mo-Sci Corporation (Rolla, Missouri, USA) for wound healing (DermaFuse™/Mirragen™)4,6. Tiny cotton-like fibers are drawn out from the bioactive glass. A scaffold is produced by the fibrous network, similar to the natural fibrin scaffold formed by the body, to encourage wound healing. There is high calcium content in the glass because this mineral is essential to promote skin regeneration. It has been shown that the fibrous borate bioactive glass is effective and help heals long-term venous stasis ulcers. It is being hoped that this glass will also be equally effective for treating burns and other extensive wounds.

Bioactive glass in wound healing

At Phelps County Regional Medical Center, USA, a clinical trial was performed that demonstrated that DermaFuse (now known as Mirragen™) was highly effective in diabetic ulcer patients at an increased risk of limb amputation. Among the 13 participants, some had wounds that had not healed for over a year. When the wound was packed for a few months with the fibrous borate glass, the skin was completely healed in eight patients while showed considerable improvement in the other four participants. In fact, the healed skin had little to no scarring.

Earlier this year, this new wound healing material obtained FDA marketing approval and is also received approval for use in the veterinary field under the brand name Redi-Heal™.

Conclusion

In tissue engineering, bioactive glass serves as an important tool as it is biocompatible and also its properties can be customized to meet a specific requirement by modifying the glass’ structure and composition. For many years, bioactive glass has been used to provide a scaffold for periodontal reconstruction and bone repair, and more recently it has been widely studied in soft tissue repair.

In addition, a fibrous bioactive glass product was approved for use in wound repair earlier this year. The effective treatment of non-healing venous stasis ulcers shows that more serious skin damage such as burns may also be effectively treated.

References

- Guo S, and DiPietro LA. Factors Affecting Wound Healing. J Dent Res. 2010;89(3): 219–229.

- Nelson EA, Cullum N, Jones J. Venous leg ulcers. Clin Evid 2006;15:2607–2626.

- Xie X, McGregor M, Dendukuri N. The clinical effectiveness of negative pressure wound therapy: a systematic review. Journal of Wound Care. 2010;19 (11): 490–495.

- The American Ceramic Society Press release 4 May 2011. Available at https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/05/110503133056.htm

- Rahaman MN, Day DE, Bal S, et al. Bioactive glass in tissue engineering. Acta Biomaterialia 2011;7:2355?2373.

- Mo Sci Corporation website. http://www.mo-sci.com/bioactive-glass.html